Municipal debt markets are made up of a wide array of debt instruments and serve investors from all walks of life. Whether you are a conservative investor looking for principal protection while earning enough to keep up with inflation or a moderate risk taker who might be looking for high returns on your municipal debt portfolio, you’ll find many debt instruments to fit your client profile.

The new wave of green municipal debt instruments has many investors talking and potentially looking to make them part of their portfolio. Green munis can be either general obligation or revenue-backed debt instruments that are essentially issued to fund any “green initiative” or project by local and state governments. Many local governments have been focused on reducing carbon emissions in their infrastructure projects or conserving run-off rainwater – all of which could potentially constitute as a green project.

Furthermore, an important branch of green bonds are known as Environmental Impact Bonds (EIBs), which are starting to gain momentum with muni investors. In this article, we’ll take a closer look at EIBs and whether the increased use of these bonds will give muni investors an opportunity to earn higher returns with a risk profile similar to that of current munis.

Want to know more about green muni bonds? Click here. You can also read this to understand the rationale behind investing in these bonds.

Introduction to Environmental Impact Bonds

As the name suggests, EIBs provide municipalities with a new source of capital to build green infrastructures such as rain barrels to conserve rain water, permeable pavements, bioswales, etc., in order to have a positive impact on the environment and take the financial and resource strain off of local governments and various utilities. Many private-public partnerships are encouraging local governments to reevaluate their operations and potentially capitalize on the funding available through EIBs.

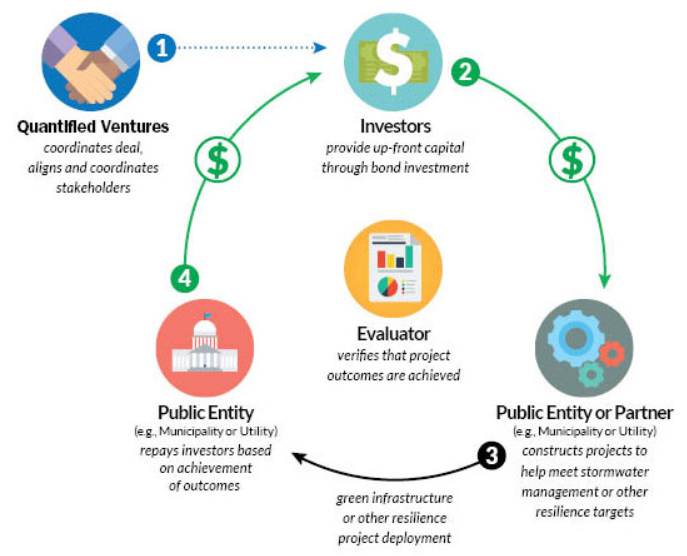

As shown in the diagram below, the EIB structure resembles a revenue-backed debt structure in which an investor’s interest and stake in a project is secured by the project’s revenues. An EIB is structured in such a way that investors are introduced to local or statewide environmental resilience projects (green infrastructure projects) for which they provide upfront funding while choosing to share the project’s revenues and risks.

EIBs are not limited to only providing funding for green initiatives for local and statewide governments; they also encourage private-public partnerships. They have emerged as a key way to obtain funding for projects that may have been difficult to finance in the past. In addition, many governments are now able to explore and pilot new and innovative projects with EIB capital that may not have been accessible through traditional bond issuances.

Check out all the different ways to invest in muni bonds to stay up to date with current investment strategies.

Debt Structure of Environmental Impact Bonds

An EIB’s structure is quite like revenue-backed debt, in which the revenue streams of a project are collateralized to meet the debt service on the municipal debt. Under an EIB’s structure, an issuance team and the municipality work together in identifying the project and its feasibility of fitting under the green bond umbrella. Once the project is deemed as an environmental resilience project then the municipality moves forward with the issuance of debt and sells it to private investors. The municipality is liable for monitoring the completion, evaluating the outcome of the project and meeting its debt service obligation to the EIB’s investors.

Many of the green initiatives like distributed water conservation infrastructures by local governments throughout the U.S. have faced legal scrutiny due to the federal tax-exemption clause associated with these debt instruments. Since distributed infrastructures encompass and extend to private properties (i.e. businesses and parking lots), it creates a legal dilemma for utilities when issuing any tax-exempt debt. Public funds or issuance of debt is meant to be used for public benefit and its use for private properties is a gray area. This will require states to amend their constitutional regulations to permit financing for distributed infrastructures.

As U.S. cities start using muni financing for their green projects – for example, New York City’s toilet buybacks and Seattle’s distributed infrastructure – state and local governments will need to consider state-level law amendments. As governments start to recognize the urgent need to adopt these measures, public finance laws will be reshaped to allow the use of muni bond funding. Until then, entities will have to constrain themselves and their work within the legal parameters (like New York and Seattle) to fund their green endeavors.

Also, public-private partnerships have played an important role in the increased volume of green transactions, have made green muni markets more liquid and provide easy access to capital.

An optimal example of EIBs emerges from Washington, DC, where local and state governments have long been looking to restore the wetlands and have been focused on water conservation and water management in general to tackle potential climate change impacts. Again, similar to New York and Seattle, where traditional funding sources have turned their backs on these innovative projects, private-public partnerships and EIBs emerged as the solution for Washington, DC. Washington’s water utility pioneered the nation’s first EIB bond offering in late 2016 when it sold a $25-million, tax-exempt EIB in a private placement to the Goldman Sachs Urban Investment Group and the Calvert Foundation.

You can discover bonds offering attractive yields using our tool here.

Risk Reward Implications of EIBs

As mentioned above, EIBs are used to fund projects that otherwise may not be able to obtain adequate capital under the traditional debt issuances; hence, they provide an opportunity for investors to capitalize on the potential higher yields of the EIBs. In addition, the investors are not only participating in a social/green investing mechanism but also working in conjunction with the local government to make the green initiatives successful.

On the flip side, there are also some inherent risks with EIBs for their investors. One of the biggest concerns is being unable to monetize the environmental benefit of the green initiatives for local governments, which could potentially impact an investor’s payout. The same scenario applies to the issuer, where it may be quite difficult for them to relate to the environmental benefit of the project and translate it into financial success.

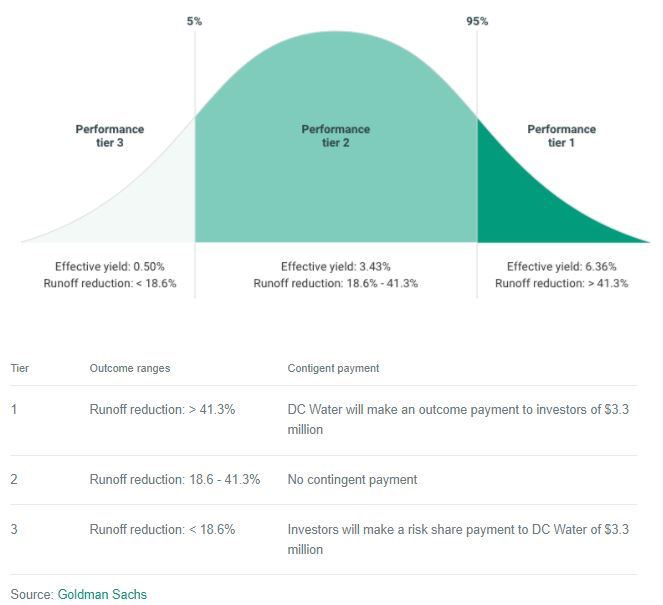

In addition, the returns on EIB instruments are determined by the outcome of the project and the various measurements of the overall performance; hence, the project risk isn’t just the burden of the local government or entity but also any private investors involved in the project. The financial payouts to these private investors are conditional and based upon the successful completion of the project and proper evaluation of its performance measures. There could also be options regarding tier-based financial output, where the private investor can capitalize on higher returns if the project performance exceeds expectations and vice versa. For instance, the tiered payout structure of the above-mentioned Washington, DC, EIB can be seen below wherein it is clearly evident that the investor stands to earn a better effective yield if the project performance (i.e., reducing stormwater runoff in this case) is better than expected.

The Bottom Line

Across the U.S., as utilities become more committed to their green efforts of conserving water, reusing stormwater and reducing wastewater, the market will become more liquid for the new wave of green munis and/or environmental impact bonds. States that have struggled with the effects of climate change will be the ones investors should keep an eye on since they will be taking the lead on green project efforts across the nation. Given the risks and rewards of EIBs, investors should carefully analyze the debt transaction, its structuring, the environmental impact and positive financial outcome of any green project/initiative.